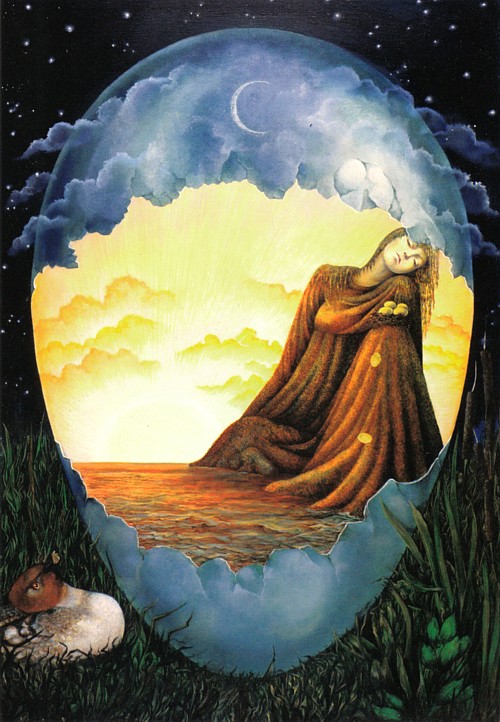

LUONNOTARTHE KALEVALA IS THE NATIONAL EPIC OF FINLAND and one of Linda's favourite tales. She's tackled it more than once so it was a natural choice for opening the Creation chapter of this book. Tales from the Kalevala have been told around winter fires for thousands of years in the frozen north of Europe, but were not gathered into a coherent whole until the nineteenth century. Their saviour was Elias Lonnrot (1802-1884) who spent many years collecting folktales in northeast Finland. Then in a piece of inspired scholarship and poetry (like Malory with the story of King Arthur) he welded the many strands together and published his definitive version in 1849. As Finland was then struggling to shake off the influence of Russia on the one side and Sweden on the other, the poem was seized on as a focus for national identity, written as it was in the tongue of the common people (the Finnish ruling class at that time mostly spoke Swedish). Over the next few decades the Kalevala played a major part in achieving Finnish independence. In fact, as folklorist William A. Wilson says in Folklore and Nationalism in Modern Finland: 'Probably in no other country has the marriage of folklore studies and nationalism produced such dramatic results as in Finland. As Prof. Jouko Hautala maintains, had it not been for the publication of Lonnrot's Kalevala and for the subsequent cultural work based on it there is good chance to believe that Finland could not have achieved independence.' The story of Creation in the Kalevala begins with the sacred bird Goldeneye flying over the dim ocean in search of somewhere to rest. But at that time there was no land, neither was there any sun or moon. There existed only the dim sky and endless ocean. Then Luonnotar, mother of the water, virgin of the air, took pity and raised her knee from the icy waters as a perch for Goldeneye. The teal circled and landed, thinking it a turf-grown cliff. And there on Luonnotar's knee she built a nest and laid seven eggs, six of gold and one of iron: |

O'er her eggs the teal sat brooding,

Then the Mother of the Waters,

Till she thought her knee was burning,

Rolled the eggs into the water,

But in ooze they were not wasted,

From a cracked egg's lower fragment

From a yolk, the upper portion,

Whatso in the egg was mottled

. . . . . . . .

When the ninth year had passed over,

And then she began Creation,

Whersoe'er her hand she pointed,

When she dived beneath the water,

Where her feet to land extended,

|